Trainspotting was the book which launched Irvine Welsh into the literary stratosphere: an incendiary, controversial exploration of Edinburgh’s heroin subculture. Characterised by Welsh’s uncanny and innovative approach to his native dialect and filled to the brim with memorably unsavoury characters, the novel remains the high watermark of Welsh’s career – so much so that he’s sought to repeat the success by revisiting the chaotic world of his Leith junkies twice - in sequel Porno and newly released prequel Skag Boys.

Around the time of novel’s release, Scotland was enjoying a cinematic renaissance – despite Mel Gibson’s best attempts to rewrite Celtic history in the lamentable Braveheart. The vastly superior Rob Roy and Danny Boyle’s blackly comic Shallow Grave both hit the silver screen in the mid-nineties to great acclaim. With the establishment of the Scottish Parliament on the horizon and even the Scottish football team in the headlines – albeit thanks to a Paul Gascoigne inspired defeat at Euro 96 – transforming Trainspotting’s source material into a movie was a no-brainer. But nobody could have anticipated the wider impact of Danny Boyle’s magnificent film.

Drawing heavily on pop-culture, Trainspotting’s appeal was worldwide: the energetically eclectic soundtrack included Britpop big hitters Damon Albarn and Pulp alongside US luminaries Iggy Pop and Lou Reed (both famed heroin users). The attractive young cast gave uniformly excellent performances and the superb mixture of gritty realism and fantastical drug sequences ensured the film had wide and enduring appeal. But 16 years on from its release, does Trainspotting truly stand the test of time?

Trainspotting sets its stall out from the outset: its characters are a bunch of reprobates and losers on the peripheries of ‘normal’ society. Their goals and desires bear little relation to what a modern audience might expect – with Mark Renton’s memorable anti-capitalist ‘choose life’ monologue playing over the opening scenes of shoplifting and one of the most inept five-a-side football performances ever committed to celluloid. It’s a fantastic introduction to the leads, freeze-framing them with their names flashed on the screen, quickly establishing their personalities and flaws as Renton’s voiceover places them deliberately and consciously outside of the norm: they might be losers, but they chose to live that way rather than live in a world they actively resent.

Renton’s speech has become famous in its own right: satirised, imitated and intoned across cultural platforms, quoted and reinterpreted, reproduced and reprinted. Ewan McGregor’s embittered delivery of the lines makes apparent the utter disdain Renton has for the mundane aspirations of the masses as he lists the insipid materialistic goals they strive for: washing machines, cars, compact disc players. For Renton, these seemingly endless choices offer no choice at all. He chooses not to choose life. And why? “Who needs reasons when you’ve got heroin?”

In that opening salvo, played to the bouncing rhythm of Iggy Pop’s Lust For Life, the tone for the film is set and the audience is already asked to question the goals and aims they have previously set themselves, forcing them to understand what drives the junkie mindset. With that in mind, Trainspotting takes a deliberate step back from moralising or passing judgement on drug consumption, trusting instead that the home audience will arrive at their own conclusions after being presented with the evidence.

Arguably Trainspotting’s most iconic scene – and certainly its most significant – occurs in an excrement-encrusted toilet cubicle. Suffering from painful junk withdrawal and with his stomach churning, Renton is forced to evacuate his bowels– including the opium suppositories he has secreted in his back passage - in ‘the worst toilet in Scotland’. Retching and gagging, he’s forced to plunge his hands into the filthy toilet bowl, gradually disappearing head first into the lavatory – only to emerge on the other side in a clear blue sea. Brian Eno’s beautiful Deep Blue Day soundtracks the scene as Renton swims serenely to the ocean floor to retrieve the suppositories – shimmering and glimmering like pearls on the sea-bed.

It’s a wonderfully effective scene, juxtaposing the filth and depravity of heroin dependence with the clarity and ecstasy of being utterly, wonderfully wasted. For many, the disgust and revulsion of Renton’s shit-stained desperation is nauseating – but for him the pay-off is worth it. Too often, films shy away from the realities of drug taking and fail to illustrate the positive effects they have on their takers. Here, Danny Boyle gives a perceptive and brave insight into why people seek such highs and the depths they are willing to plumb to do so. As Renton himself observes, "People associate it with misery, desperation and death, which is not to be ignored. But what they forget is the pleasure of it, otherwise we wouldn't do it.”

That Trainspotting manages to be so insightful and thought provoking is remarkable given its compact running time. In just over ninety minutes it manages to cram in enormous numbers of well-drawn characters, set-pieces and storylines. Although screenwriter John Hodge and Danny Boyle dispensed with whole characters and vast swathes of Welsh’s original narrative, the film is an uncannily accurate representation of the novel.

Hodge and Boyle’s excellent screenplay and direction are, of course, key in this. But perhaps even more important are the performances of the cast. Star-making turns from Ewan McGregor, Jonny Lee Miller and Robert Carlyle imbue their characters with power, wit and verve scarcely seen in such ensemble casts. Carlyle, particularly, creates a monstrously memorable character in Begbie: a swaggering, amoral alcoholic dispensing his own unique brand of hypocritical advice to all and sundry.

Given Carlyle’s diminutive physical stature, to present such a convincingly violent sociopath is quite some achievement. His mastery of the Scottish dialect clearly helps - not least in his guttural pronunciation of the word ‘cunt’. But the real strength of his performance is in his wildly expressive eyes: shifty, suspicious, menacing and fearful in equal measure. It’s a revoltingly hypnotic mask – made all the more grotesque by his absurd moustache. In a movie brimming with memorable characters, he’s the one who lingers longest in the mind.

Granted, Begbie is an overblown caricature. But, like the film’s other characters, he is worryingly real. Elements of Sick Boy, Tommy, Spud, Renton et al are instantly recognisable, however exaggerated. They are deeply flawed and immoral young men who, thanks to some wonderfully charismatic and committed performances, remain endearingly sympathetic: especially Ewan Bremner’s hapless Spud – ironically the actor with the least successful post-Trainspotting career.

Underpinning the storyline and the characters is Trainspotting’s superb soundtrack. Lust For Life roared back into the charts on the back of the film’s success, thrusting Iggy Pop (a reference point throughout) back into the limelight, Lou Reed’s Perfect Day become a morose pub anthem and Underworld’s Born Slippy became the tune of choice for binge drinkers all over the world. But the song-selection was far more subtle at times: changing drug cultures were signposted through song, the characters’ sensory addictions were mirrored in music and Spud’s heartfelt singing at Tommy’s wake unites the characters in their futile grief.

Voiceover, too, plays a huge part. Often films with vast swathes of narration lack dynamism, but combined with flurries of short scenes, swift editing, music and exaggerated sound effects, Trainspotting avoids such pitfalls. Indeed, sound effects play a significant role in drawing the audience into the pop counter-culture depicted: Renton’s gurgling bowels, Spud’s slurped milkshake and Begbie’s torn pool table all succeed in blanking out the outside world and focusing attention on the pathetic minutiae of their small-time lives.

What really cemented Trainspotting in viewers’ minds, however, was way it tapped into the cultural zeitgeist. The cross-generational soundtrack reflected the derivative Britpop sound of the mid-nineties as well as utilising some of its biggest and best acts: the aggressively marketed and hugely successful OST (and its second volume) was almost as ubiquitous as the iconic poster campaign.

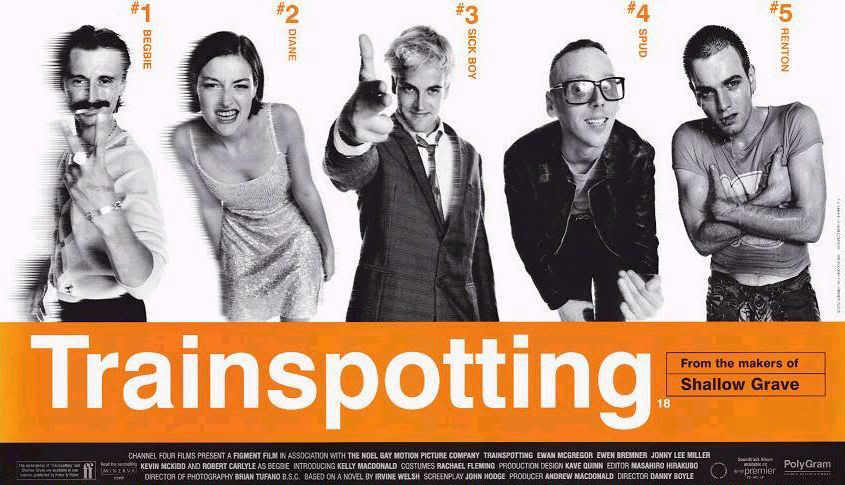

Nothing more than black and white stills of the characters and bold orange text, the poster became instantly recognisable and was endlessly and shamelessly ripped off. Designers Stylorouge were determined to reflect the multiple identities of the film’s characters and the disparate and separate narratives of the novel: individual shots in montage fulfilled the brief perfectly. The stunningly simple design said little about the movie and was, accordingly, a big risk – which paid off handsomely in the form of numerous design and industry awards.

Whilst Boyle has occasionally talked of reuniting the cast to film Porno, McGregor is not at all keen. For this, we should be grateful. Repeating the success of Trainspotting would be impossible. It’s a film totally of its time but utterly timeless. Its intertextual blend of drug culture, music, sport and cinema references was and is perfect: the greatest ever screen depiction of youth culture will never grow old.

Very good, Mr.Ward. I enjoyed that. A dam fine read about a dam fine film.

ReplyDeleteMike